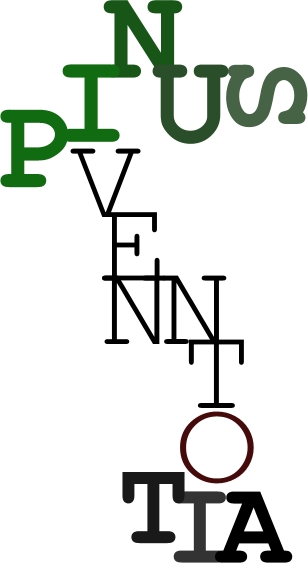

To wygląda na zagajnik

pinusowy – trzy drzewa pinusowe obok siebie. Oczywiście,

gdyby były cztery drzewa, wyglądałoby to bardziej

zagajnikowo niż teraz. Gdyby jednak były tylko dwa drzewa,

wcale nie dałoby się pisać o jakimkolwiek zagajniku, nawet

najrzadszym... Wygląda więc na to, że trzy drzewa to

minimalna liczba drzew, która pozwala na użycie słowa zagajnik. Zapewne jednak liczba to nie

wszystko – ważna jest też odległość między drzewami, a ta

nie może być ani zbyt mała, bo wówczas mielibyśmy do

czynienia ze zwykłą kępą, ani zbyt duża, wtedy bowiem trudno

byłoby zauważyć, że to jakaś grupa.

Na znacznie bardziej skomplikowaną wygląda sprawa przymiotnika „pinusowy”, aczkolwiek powinna być znacznie prostsza niż problem rzeczownikowy, czyli wybór między kępą a zagajnikiem. Otóż, obecność słowa pinus, które zdaje się pełnić rolę korony, jak i fakt, że pnie (lub to co można by uznać za pnie) są zbudowane z tych samych liter, aczkolwiek w zupełnie różnych układach, sugerowałyby, że to drzewa tego samego gatunku, choć różnych odmian indyjsko-portugalskich, lub różnych gatunków, lecz tego samego rodzaju. Nawet gdyby ten trop, spowodowany jak najbardziej trafnymi spostrzeżeniami, okazał się dosyć prawdopodobny, należałoby zachować jak najdalej idącą ostrożność, albowiem ów trop, tak zachęcający na początku, może się okazać potem całkiem mylny i doprowadzić nas donikąd, lub do zagajnika manowców.

Wystarczy pamiętać o tym, jak wielce te drzewa różnią się pokrojem, jak zupełnie inne mają pnie, jak niepodobnie rozrośnięte gałęzie... Dobrze też przypomnieć sobie o jakże prostym fakcie, że to co wewnętrznie takie samo, lub bardzo podobne, na zewnątrz może przybierać formy diametralnie różne – i na odwrót: to co zewnętrznie takie samo, lub bardzo podobne, wewnątrz może być całkowicie niepodobne.

Na znacznie bardziej skomplikowaną wygląda sprawa przymiotnika „pinusowy”, aczkolwiek powinna być znacznie prostsza niż problem rzeczownikowy, czyli wybór między kępą a zagajnikiem. Otóż, obecność słowa pinus, które zdaje się pełnić rolę korony, jak i fakt, że pnie (lub to co można by uznać za pnie) są zbudowane z tych samych liter, aczkolwiek w zupełnie różnych układach, sugerowałyby, że to drzewa tego samego gatunku, choć różnych odmian indyjsko-portugalskich, lub różnych gatunków, lecz tego samego rodzaju. Nawet gdyby ten trop, spowodowany jak najbardziej trafnymi spostrzeżeniami, okazał się dosyć prawdopodobny, należałoby zachować jak najdalej idącą ostrożność, albowiem ów trop, tak zachęcający na początku, może się okazać potem całkiem mylny i doprowadzić nas donikąd, lub do zagajnika manowców.

Wystarczy pamiętać o tym, jak wielce te drzewa różnią się pokrojem, jak zupełnie inne mają pnie, jak niepodobnie rozrośnięte gałęzie... Dobrze też przypomnieć sobie o jakże prostym fakcie, że to co wewnętrznie takie samo, lub bardzo podobne, na zewnątrz może przybierać formy diametralnie różne – i na odwrót: to co zewnętrznie takie samo, lub bardzo podobne, wewnątrz może być całkowicie niepodobne.

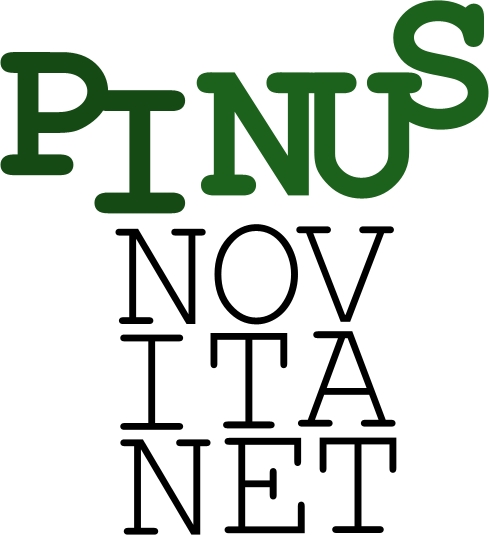

It looks like this is a pinus grove – three pinus

trees one beside the other. Of course, if there were four

trees, this would look more like a grove... more grovy – but

not more groovy... However, if there were only two trees, I

could write about no grove at all, even extremely thin... So,

it looks like three is the smallest number of trees allowing

us to use the word grove. But the number alone does

not suffice, no doubt about it – the distance between the

trees is important, too; the distance can be neither too small

(then we would have but a clump), nor too big (then we

wouldn't notice any group).

The word pinus seems to be much more complicated matter than making a choice between grove and clump. Well, the presence of pinus, which seems to be something like a crown, as well as the fact that the trunks (or what can be considered the trunks) are composed of the same letters, although appearing in different combinations, which would suggest these are the trees of the same species, but of different varieties, with no doubt Indian-Portuguese, or of various species but of the same genus. Even if this track-trail-trope, being result of quite right observations, turned out to be very probable, we should be extremely careful, because so encouraging in the beginning it can lead us to nowhere... Does it mean: to NO place? Is there a place which is NO place? An antiplace? Extremely interesting, isn't it?

It's enough to remember, how different are the silhouettes of these tress, their outlines, their trunks, their branches... It's good to remember that what is the same, or very similar, internally, can have absolutely different external forms – and vice versa: what is the same externally, or very similar, can be absolutely not the same internally.

Nu, ĉu povas esti, ke jen arbareto? Tri arboj pinusaj, unu apud alia – do la pinusareto. Kompreneble, se estus kvar arboj, tio aspektus pli arbarete ol nun, eble eĉ arbare. Tamen, se estus nur du arboj, tiam oni ne povus verki pri arbaro, eĉ la plej eta, eteta, eteteta... Do, ŝajnas, ke tri arboj jen la minimuma kvanto, kiu permesas al ni uzi la vorton arbareto. Tamen ne nur la kvanto gravas – sendube gravas ankaŭ la distanco inter arboj kaj ĝi povas esti nek tro malgranda, ĉar tiam ni havus la tufon, prefere arbotufon, nek tro granda, ĉar tiam ni simple ne rimarkus, ke temas pri aro.

Pli komplika ŝajnas la problemo de adjektivo pinusa, kvankam ĝi devus esti multe malpli komplika ol la problemo de substantivoj (tufo aŭ aro?). La ĉeesto de vorto pinus, kiu ŝajnas ludi la rolon de branĉaro, korolo, kaj la fakto, ke la trunkoj (aŭ tio kion oni povas konsideri trunkojn) estas konstruitaj el la samaj literoj, kvankam kombinitaj kaj komponitaj tute malsame, sugestus ke jen la arboj de la sama specio, sed de diversaj variaĵoj, hindiaj-portugalaj, aŭ de diversaj specioj, sed de la sama familio. Eĉ se tiu tropo, kaŭzita de vere trafaj observaĵoj, montriĝus sufiĉe probabla, oni devus esti ege atentaj, ĉar la tropo, komence tiel alloga, baldaŭ povas montriĝi tute erara kaj gvidi nin nenien (do al NENIU loko – vere io tre interesega: la loko kiu estas malloko, la neloko...)

Sufiĉas memori, ke tiuj arboj havas diversajn siluetojn, malsamajn konturojn, nesimilajn trunkojn kaj branĉarojn.... Estas bone memori, ke tio kio interne estas sama, aŭ ege simila, ekstere povas havi ekstreme diversajn formojn – kaj inverse: tio kio ekstere estas sama, aŭ ege simila, interne povas esti tute malsama.

The word pinus seems to be much more complicated matter than making a choice between grove and clump. Well, the presence of pinus, which seems to be something like a crown, as well as the fact that the trunks (or what can be considered the trunks) are composed of the same letters, although appearing in different combinations, which would suggest these are the trees of the same species, but of different varieties, with no doubt Indian-Portuguese, or of various species but of the same genus. Even if this track-trail-trope, being result of quite right observations, turned out to be very probable, we should be extremely careful, because so encouraging in the beginning it can lead us to nowhere... Does it mean: to NO place? Is there a place which is NO place? An antiplace? Extremely interesting, isn't it?

It's enough to remember, how different are the silhouettes of these tress, their outlines, their trunks, their branches... It's good to remember that what is the same, or very similar, internally, can have absolutely different external forms – and vice versa: what is the same externally, or very similar, can be absolutely not the same internally.

Nu, ĉu povas esti, ke jen arbareto? Tri arboj pinusaj, unu apud alia – do la pinusareto. Kompreneble, se estus kvar arboj, tio aspektus pli arbarete ol nun, eble eĉ arbare. Tamen, se estus nur du arboj, tiam oni ne povus verki pri arbaro, eĉ la plej eta, eteta, eteteta... Do, ŝajnas, ke tri arboj jen la minimuma kvanto, kiu permesas al ni uzi la vorton arbareto. Tamen ne nur la kvanto gravas – sendube gravas ankaŭ la distanco inter arboj kaj ĝi povas esti nek tro malgranda, ĉar tiam ni havus la tufon, prefere arbotufon, nek tro granda, ĉar tiam ni simple ne rimarkus, ke temas pri aro.

Pli komplika ŝajnas la problemo de adjektivo pinusa, kvankam ĝi devus esti multe malpli komplika ol la problemo de substantivoj (tufo aŭ aro?). La ĉeesto de vorto pinus, kiu ŝajnas ludi la rolon de branĉaro, korolo, kaj la fakto, ke la trunkoj (aŭ tio kion oni povas konsideri trunkojn) estas konstruitaj el la samaj literoj, kvankam kombinitaj kaj komponitaj tute malsame, sugestus ke jen la arboj de la sama specio, sed de diversaj variaĵoj, hindiaj-portugalaj, aŭ de diversaj specioj, sed de la sama familio. Eĉ se tiu tropo, kaŭzita de vere trafaj observaĵoj, montriĝus sufiĉe probabla, oni devus esti ege atentaj, ĉar la tropo, komence tiel alloga, baldaŭ povas montriĝi tute erara kaj gvidi nin nenien (do al NENIU loko – vere io tre interesega: la loko kiu estas malloko, la neloko...)

Sufiĉas memori, ke tiuj arboj havas diversajn siluetojn, malsamajn konturojn, nesimilajn trunkojn kaj branĉarojn.... Estas bone memori, ke tio kio interne estas sama, aŭ ege simila, ekstere povas havi ekstreme diversajn formojn – kaj inverse: tio kio ekstere estas sama, aŭ ege simila, interne povas esti tute malsama.